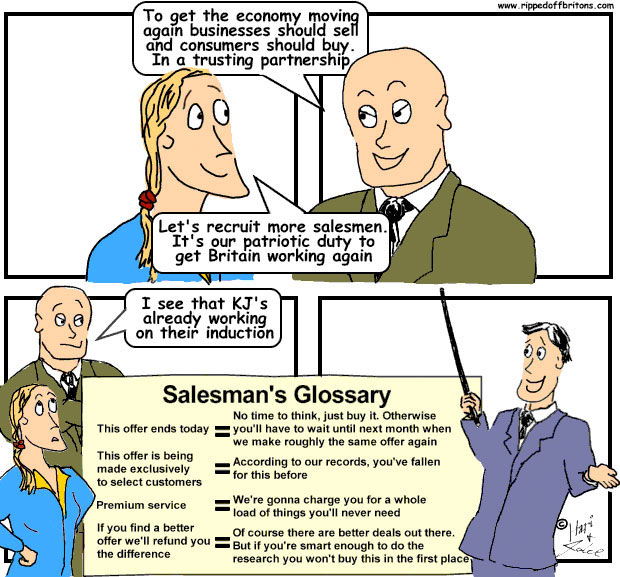

Posted by Jake on Sunday, October 23, 2011 with 5 comments | Labels: advertising, Article, banks, Big Society, education, inequality, OFT, regulation, sales techniques, the courts, the government

The right to rip-off Britons is enshrined in British law, most explicitly by the ironically named “Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations”. It is not our contention that the rip-offs we write about in this blog are illegal – just that they are rip-offs. But that is the problem: as you will read in the rest of this blog, the rip-offs are not in breach of the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations so long as they rip-off no more than half their target market.

The right to rip-off Britons is enshrined in British law, most explicitly by the ironically named “Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations”. It is not our contention that the rip-offs we write about in this blog are illegal – just that they are rip-offs. But that is the problem: as you will read in the rest of this blog, the rip-offs are not in breach of the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations so long as they rip-off no more than half their target market.The preamble in this legislation tells us that the law will protect the “average consumer” (and of course all those smarter or better informed than average). It helpfully goes on to qualify this “average consumer” as being “reasonably well informed, reasonably observant and circumspect”.

It further states that:

“In determining the effect of a commercial practice on the average consumer where the practice is directed to a particular group of consumers, a reference to the average consumer shall be read as referring to the average member of that group.”

...going on to say:

“(a) where a clearly identifiable group of consumers is particularly vulnerable to the practice or the underlying product because of their mental or physical infirmity, age or credulity in a way which the trader could reasonably be expected to foresee,

and

and

(b) where the practice is likely to materially distort the economic behaviour only of that group,

a reference to the average consumer shall be read as referring to the average member of that group”

Thus, in words comprehensible to the average trader, the legislation makes clear that the trader is permitted to rip off the "below average" half of the population.

The act goes on to stipulate explicitly what a trader may and may not do:

- A commercial practice is unfair if…..it materially distorts or is likely to materially distort the economic behaviour of the average consumer with regard to the product.

- A commercial practice is a misleading action if…. it causes or is likely to cause the average consumer to take a transactional decision he would not have taken otherwise.

- A commercial practice is a misleading omission if, in its factual context…. it causes or is likely to cause the average consumer to take a transactional decision he would not have taken otherwise.

- A commercial practice is aggressive if….it significantly impairs or is likely significantly to impair the average consumer’s freedom of choice or conduct in relation to the product concerned through the use of harassment, coercion or undue influence

The act continues that a trader is guilty of an offence if:

- (a) he knowingly or recklessly engages in a commercial practice which contravenes the requirements of professional diligence under regulation 3(3)(a);

and

- (b) the practice materially distorts or is likely to materially distort the economic behaviour of the average consumer with regard to the product under regulation 3(3)(b).

Never underestimate the power of an “and”. Einstein, in one of his quips about the world we live in, thought compound interest was the most powerful force in the universe. I think it is “and”, and/or perhaps “or”. Two little words that make almost anything possible. In this case the “and” tells us that the trader is legally allowed to use any tactic he wants, be it unfair, misleading, aggressive, reckless, unprofessional so long as the “average consumer” won’t be tricked by them. Anyone “less than average” is fair game to be recklessly coerced, misled, and handled unfairly. On them it’s open season 12 months a year!

To understand the implications of the legislation:

To understand the implications of the legislation:

If we lined our population up in order of each one’s ability to do hard sums and understand tricksy small-print in a ‘terms and conditions’ contract putting the smartest in Edinburgh with the line heading south to London, the average guy would be the one in the middle, in the city of Leeds.

The laughably called “consumer protection” legislation leaves unprotected the half of the population lined up south of Leeds in this map:

So, how easy is it to trick an “average consumer”?

Well, the UK government did a revealing study in 2003, “The Skills for Life survey”. The purpose of the survey was to understand the literacy and numeracy skills in the UK population. To achieve this, the survey classified people according to their level of academic ability.

For our overseas readers, and some of our fellow ripped-off Britons who haven’t had to have anything to do with school for a while, here is a bit of base information you will need to understand the graphs below:

National Approximate School

Standard Level Equivalent

Entry 1 Key stage 1 (ability expected of a student age 5-7)

Entry 2 Key stage 2 (ability expected of a student age 7-9)

Entry 3 Key stage 2 (ability expected of a student age 9-11)

Level 1 GCSE D-G (ability expected of a student age 11-14)

Level 2 GCSE A*-C (ability expected of a student age 14-16)

GCSE = General Certificate of School Education, usually taken by 15-16 year olds in the UK. Students can achieve pass grades from A* at the top down to G, or else fail the test.

The Skills for Life survey looked into the literacy and numeracy levels of the UK population and found the following:

In real numbers

Literacy: 16% at Entry Level 3 and below = 5.2 million adults

Reading age of 11 years and below.

Numeracy: 46% at Entry Level 3 and below = 15 million adults

Numeracy age of 11 years and below.

Across Britain, those who fall into the “less than average” group, unprotected by the “Consumer Protection” legislation, include millions of people who have the mathematical and reading ability of a junior school child. Banks, energy companies, insurers, mobile phone companies, and all the other lawful businesses in Britain have a free hand with these Britons.

You may think that this bottom 50% probably don’t have enough money to make them worth ripping-off. You would be wrong. Confusing money with wealth is a mistake the blue-chips don’t make. They understand that while the bottom 50% of the population have negligible wealth, they do 30% of the nation’s spending (figures from the Office of National Statistics).

30% of all the spending in Britain is a lot of money. And the courts look very sympathetically on organisations that go hunting this “less than average” customer base – as the banks found when they defeated the Office of Fair Trading in their case against excessive bank charges. Throwing out the OFT’s case, their lordships stated:

So long as the contract gives the terms and conditions somewhere, in language that is “plain and intelligible” to the “average” customer then it doesn’t matter how great or grotesque the rip-off is. In law it cannot be said to be “unfair”, and is therefore “fair”.

And that’s the law in Ripped-Off Britain.

Consumer Minister Edward Davey said, in statement on 19th Oct 2011:

ReplyDeletehttp://nds.coi.gov.uk/content/Detail.aspx?ReleaseID=421254&NewsAreaID=2

"Current aggressive practices include:

-implying a connection with social services or an old age charity;

-preying on the elderly person’s fear of losing their independence;

-writing out cheques or an order form for the victim;

-salespersons refusing to leave the premises until they have secured a sale.

Simplify the law: Ask 'does the customer feel like they've been ripped off?' If the answer is 'Yes', then give them back their money.

ReplyDeleteBut that approach means that nobody has to take responsibility for their own actions. . . I make an informed decision to buy a coat, and buy it. . . wear it a few times, maybe get it dirty and then decide it was a rip off and get my money back leaving the (possibly honest) retailer out of pocket.

DeleteWhat's needed is much tighter laws about what is genuinely bad sales practice and misleading advertising. If you make sure businesses will genuinely pay for ripping people off then there's no need to declare open season for chancers to rip off businesses in return either

The provisons of the Consumer Rights Directive must become law in every EU state by the end of 2013.

ReplyDeleteSome parts of the forthcoming changes were recently published in the Draft Bill on Consumer Rights.

The rest will follow in numerous pieces of secondary legislation later in the Autumn.

This legislation is a complete shake-up of consumer legislation in the UK.

This isn't saying it's ok to rip-off vulnerable people. It's saying that if a practice is able to dupe someone of even 'average' intelligence then it is bad.

ReplyDelete