The right to rip-off Britons is enshrined in British law, most explicitly by the ironically named “Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations”. It is not our contention that the rip-offs we write about in this blog are illegal – just that they are rip-offs. But that is the problem: as you will read in the rest of this blog, the rip-offs are not in breach of the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations so long as they rip-off no more than half their target market.

The right to rip-off Britons is enshrined in British law, most explicitly by the ironically named “Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations”. It is not our contention that the rip-offs we write about in this blog are illegal – just that they are rip-offs. But that is the problem: as you will read in the rest of this blog, the rip-offs are not in breach of the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations so long as they rip-off no more than half their target market.

The preamble in this legislation tells us that the law will protect the “average consumer” (and of course all those smarter or better informed than average). It helpfully goes on to qualify this “average consumer” as being “reasonably well informed, reasonably observant and circumspect”.

It further states that:

“In determining the effect of a commercial practice on the average consumer where the practice is directed to a particular group of consumers, a reference to the average consumer shall be read as referring to the average member of that group.”

...going on to say:

“(a) where a clearly identifiable group of consumers is particularly vulnerable to the practice or the underlying product because of their mental or physical infirmity, age or credulity in a way which the trader could reasonably be expected to foresee,

and

(b) where the practice is likely to materially distort the economic behaviour only of that group,

a reference to the average consumer shall be read as referring to the average member of that group”

Thus, in words comprehensible to the average trader, the legislation makes clear that the trader is permitted to rip off the "below average" half of the population. If the trader, be he a high-street banker or a purveyor of sweeties, is selling specifically to a mentally infirm or credulous group then he is permitted to rip off the more infirm and credulous half of the group.

The act goes on to stipulate explicitly what a trader may and may not do:

- A commercial practice is unfair if…..it materially distorts or is likely to materially distort the economic behaviour of the average consumer with regard to the product.

- A commercial practice is a misleading action if…. it causes or is likely to cause the average consumer to take a transactional decision he would not have taken otherwise.

- A commercial practice is a misleading omission if, in its factual context…. it causes or is likely to cause the average consumer to take a transactional decision he would not have taken otherwise.

- A commercial practice is aggressive if….it significantly impairs or is likely significantly to impair the average consumer’s freedom of choice or conduct in relation to the product concerned through the use of harassment, coercion or undue influence

The act continues that a trader is guilty of an offence if:

- (a) he knowingly or recklessly engages in a commercial practice which contravenes the requirements of professional diligence under regulation 3(3)(a);

and

- (b) the practice materially distorts or is likely to materially distort the economic behaviour of the average consumer with regard to the product under regulation 3(3)(b).

Never underestimate the power of an “and”. Einstein, in one of his quips about the world we live in, thought compound interest was the most powerful force in the universe. I think it is “and”, and/or perhaps “or”. Two little words that make almost anything possible. In this case the “and” tells us that the trader is legally allowed to use any tactic he wants, be it unfair, misleading, aggressive, reckless, unprofessional so long as the “average consumer” won’t be tricked by them. Anyone “less than average” is fair game to be recklessly coerced, misled, and handled unfairly. On them it’s open season 12 months a year!

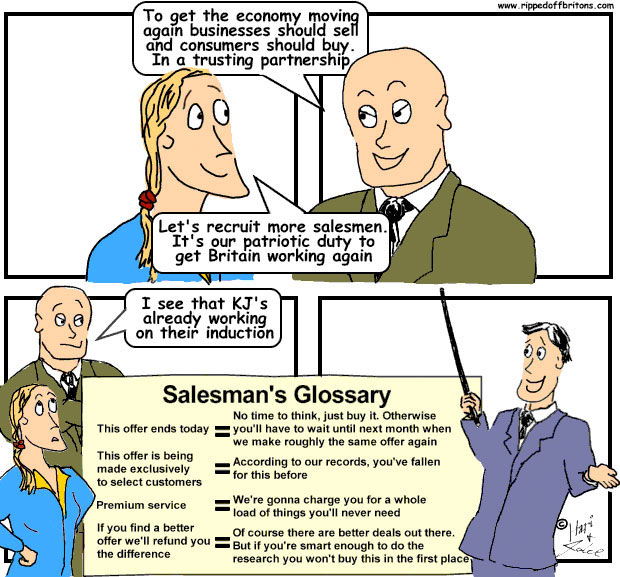

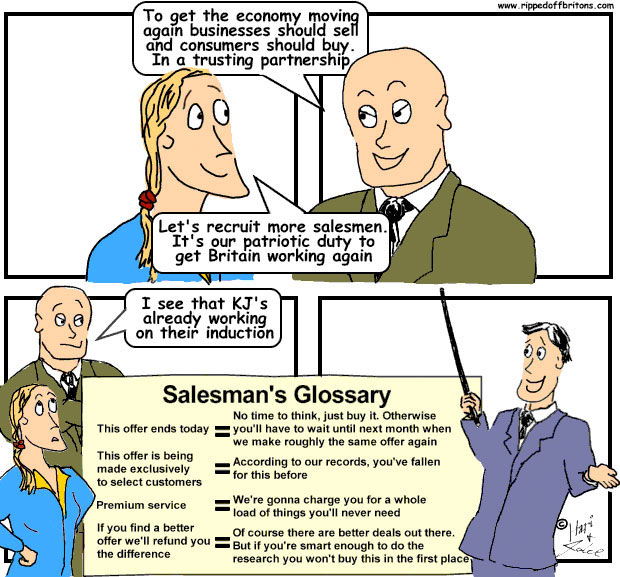

To understand the implications of the legislation: